This story originally appeared in Wake Living magazine

By John Trump

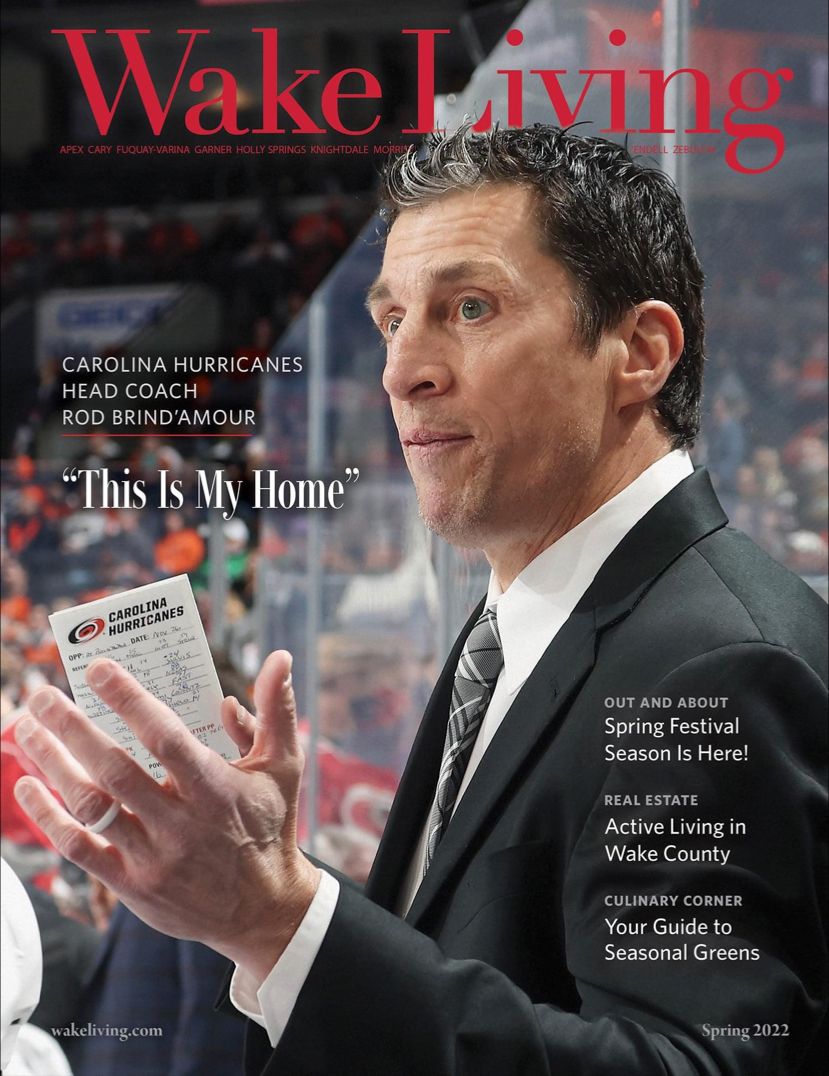

Rod Brind’Amour is a North Carolinian. The words—his words—are clear and direct. Blunt, even. “I’ve been here since January of 2000,” he says, a simple statement of fact. “I’ve been here 22 years now. My wife’s from here. We’ve got four kids; we raised them all here.”

The roots, strong, unwavering and secure, have taken hold. In one way, perhaps, a reward for something once broken but now healed.

Brind’Amour, who played 20 seasons in the National Hockey League, became head coach of the Carolina Hurricanes in May 2018. Now 51, he led the Canes to a 120-66-20 record in his first three seasons and, in 2020-21, won the Jack Adams Award as the NHL’s coach of the year. Most recently, Brind’Amour was named the Metropolitan Division head coach for the 2022 NHL All-Star game in Las Vegas.

Drafted by the St. Louis Blues, the Ottawa, Ontario, native made his NHL debut in the 1989 Stanley Cup Playoffs, where he also scored his first goal, according to NHL.com.

In 1991, the Blues traded Brind’Amour to the Philadelphia Flyers, where he established himself as an offensive star and a rugged, take-no-prisoners defender. Brind’Amour spent eight full seasons with the Flyers, and at one point played in 484 consecutive games.

Then it ended, that incredible streak.

Whether because of a stinging wrist shot or an errant pass is unclear. The streak, because of that puck—that hard, frozen and unforgiving disk—was over. Fate, we know, has a way of getting in the way of things, of rudely making junk of our plans.

But, should we allow a moment for our minds to drift and to wander, maybe fate, however curious, also has a way of knowing what’s best.

“The reason I got to Carolina and made this my home is because I got injured,” Brind’Amour told Wake Living.

Brind’Amour hadn’t missed a game since Feb. 22, 1993, until, during a preseason game Sept. 25, 1999, against the New Jersey Devils, he took that puck to the foot, the Associated Press reported at the time.

“It broke my foot, but we didn’t really know it was broke, because back then we didn’t have as good a care as we do now. So it was like, it might be a crack, you might be able to play,” says Brind’Amour, recalling conversations with Flyers’ staff. “I had the streak going…I wanted to get in there and keep it going. So, instead of just laying off the foot for two weeks—and I would have been fine—I tried to play through it and, basically, all the bones just shattered in there. All of a sudden I’m out now, and then we had a little botched surgery,” Brind’Amour says while trailing off, remembering.

“Next thing you know, I’m out for three months. Well, you’re out of sight, out of mind. I went from being a pretty big cog up there, and I think entrenched, and now I’m out for three months. Then, when I got healthy, they traded me.”

To Carolina, on Jan. 23, 2000. He hasn’t left. He doesn’t plan to.

The Hurricanes named Brind’Amour captain before the 2005-06 season, and he had his best offensive season since 1998-99, finishing with 70 points and winning the first of two Selke trophies as the league’s best defensive forward, according to NHL.com. That season, the Hurricanes, who came to North Carolina from Hartford, Connecticut, in 1997, won their first—and to this point, only—Stanley Cup championship.

“The injury got me out of Philadelphia, but it got me down here now,” he says. “I’m so grateful for it. It’s kind of funny how that works.”

Brind’Amour admittedly had an uneven start with the Canes. He hurt the foot again, but played through it because, well, that’s what hockey players, especially those good enough for talk of the Hall of Fame, do.

“So,” he says, “it was a rough start, but the injury got me here. And I’m grateful for that move.”

Brind’Amour last played with the Hurricanes in 2010. A year later, Carolina named him an assistant coach, a role he kept until becoming the franchise’s— that includes the Hartford Whalers— 14th head coach.

He’s the only head coach in franchise history, the team’s website says, to lead the Hurricanes/Whalers to a playoff berth in each of his first three seasons. The Canes, as of late January, were at the front of a four-team race for the Metropolitan Division, sharing space with the Pittsburgh Penguins, New York Rangers and Washington Capitals. Expect those top four teams to trade places, probably several times, before the playoffs start in May.

“Our division is, by far, the toughest division,” Brind’Amour says, his tone portraying more fact than opinion. “We still have more than half a year of the regular season, and we’re trying to keep that (going). We…go hard every night, and that’s the challenge, to be able to stay on the gas throughout the whole year. We don’t have a choice.

“It’s just how it is.”

That phrase, for Brind’Amour, comes out easy, eloquent in its simplicity, yet foreboding in its implications. The pandemic, for instance, is no longer only a source of incessant disruption and nagging anxiety, but also a big part of our lives, albeit an uncomfortable, unsettling one.

The NHL paused the 2019-20 season because of concerns over COVID-19, then restarted several months later in an unprecedented way, with a truncated schedule and, for each team, a small list of common opponents. Without fans but with daily COVID tests and a series of exasperating, stringent protocols.

The start of the 2020-21 season was delayed until January; the schedule trimmed from 82 games to 56. The current season marks a relative return to normalcy.

Kinda, sorta.

Just how it is.

“We’ve been dealing with it now for almost two years,” Brind’Amour says of playing through the pandemic. “It’s really made you focus on the day-to-day. You can’t really plan too far down the road, because it just never works out.

“We’re always ready to adjust to something.”

At one point in mid-January, Brind’Amour says, only six players throughout the Carolina organization had yet to contract COVID, which, in today’s oft-tumultuous world of professional sports, is a good thing.

From the once pitch-black, Brind’Amour sees that little flicker of light. “We played a couple of games (when) we were short players, and it was kind of a mess. But the league figured it out, and now we have the ability to call up as many guys as we need to fill the spot.”

Expect the unexpected. Then deal with it.

“I see there’s a little light at the end of the tunnel here with us, as far as the league and the planning process. I think it’s based on how they’re doing all this testing stuff coming up in the next month.

“We have one guy (out) now, and we had one guy last week,” Brind’Amour said in mid-January. “One guy out is not the end of the world. That doesn’t take a lot of adjusting. We had the one case last month, or maybe a month and a half ago, (when) we had six guys at one time. That’s when you get in a bit of a jam.”

COVID has also wrecked some NHL players’ plans for the 2022 Winter Olympics. The NHL won’t allow players to travel to China to play in the games, a decision, a league news release says, “made because the regular-season schedule has been disrupted as a result of increasing COVID-19 cases and a rising number of postponed games.”

“Our focus and goal have been, and must remain, to responsibly and safely complete the entirety of the NHL regular season and Stanley Cup Playoffs in a timely manner,” Commissioner Gary Bettman said in a statement.

Brind’Amour took part in the 1998 Nagano games as a member of Team Canada. He can empathize with the players who will miss out this year—Canes stars such as Sebastian Aho, Andrei Svechnikov and Nino Niederreiter.

But, says the coach, their Olympic experience would not be similar to his own. COVID won’t let that happen.

“It was a great experience, and I would want all the players to have that at some point,” he said. “However, part of the Olympic experience is being able to actually enjoy it. To not just play your games and go back to the hotel room, but to watch other events, see other athletes. To kind of just see how it is.

“This is not what’s going to happen. Add on the fact that all the unknowns of guys getting stuck over there, if they actually pick up COVID. They all kind of say, ‘Oh, I’m disappointed,’ but it’s one of those (things) where you’re kind of happy someone else made the decision because that was the right decision—to pull out of that. There’s just too many unknowns and uncertainties for everybody. The times we live in, you’ve got to make the right decision, and I think the league did.”

The duties and focus for a head coach, in the NHL or any other professional sport, for that matter, shift by the hour or even minute. But the essential focus, to win a championship, is decidedly singular.

For “small-market” teams, such as the Hurricanes, the challenge of gaining and maintaining a fan base is constant and unwavering. A ranking by Sports Media Watch of the 115 U.S.-based franchises in the “Big Four” sports leagues, according to Nielsen TV market size, has Raleigh- Durham 24th among 69 cities. New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, unsurprisingly, head the list. Memphis, Buffalo and Green Bay-Appleton, with just one or two big-league teams, are stuck in the back.

“There’s not many small-market areas, I don’t care where you are … (that) if you don’t have success you’re not going to have a huge following. You’re just not, unless, you’re in a huge, huge city.”

The Hurricanes, after their championship season in 2006, made the playoffs two years later, advancing to the conference finals before losing to Sidney Crosby and the Penguins, who went on to win the Stanley Cup. It was nine more seasons before Carolina returned to the post-season: The season Brind’Amour was named head coach.

“I think it’s very important to stay competitive and relevant for this community,” Brind’Amour says. “I mean, we know it’s a small market, we know that. We’ve been building the last few years, and the goal was to provide an entertaining team that people can have fun to watch, but (also) be proud of the way they play, because that’s kind of what we owe to the people here. We have to keep them entertained. I think we’re doing that, but we have to stay relevant. We’ve got to stay in the mix.”

Brind’Amour’s tough, relentless style when he played reverberates through this current team, as evidenced by the Canes’ nightly effort, their record and their recent trips to the playoffs. Though far removed from his playing days, Brind’Amour makes sure he plans time to work on his body, which remains striated, ripped and seemingly ready to hop over the boards for one more shift on the ice.

“It’s a routine,” he says of his workouts. “It’s no different in any job. If you want to try and stay in shape, you have to be in a routine, and you’ve got to plan it.”

He uses that gym time—in addition to staying in phenomenal shape—to watch film of the Canes and upcoming opponents, and to mentally prepare for the day, whatever that holds.

“It’s just a lifestyle,” he says. “I accomplish a lot during my workout.”

That daily routine, that daily consistency, translates into wins.

“You can have a good game here and there, and that’s great, but you have to be able to do it almost three or four nights a week, for a very long time,” Brind’Amour says. “It’s such a mental and physical grind because you have to play at a high level. Anyone can just go out and play, but if you want to win, you’ve got to play…at a highly competitive level. So, it’s being consistent every night, and that takes a lot of guys.”

It takes great leadership on the ice and in the locker room, in the end leaving no room, as Brind’Amour puts it, for guys not to play tough, smart hockey.

It’s all about consistency. That routine.

“You’ve got to have success, that’s just the way it is,” he says. “Now, we’re in a spot where our building is crazy loud, and we’ve got great fans that are really passionate about it. I think as long as we can continue to win and provide a team that gives us a chance to win every night … we’re going to be fine here.”

Here, as in home. In North Carolina, and in Raleigh, whether waiting in a line of cars to pick up his 10-year-old son from school, or to take his son to youth hockey practice. Whether heading to PNC Arena, for practice, or for a game. Or to work out or to plan.

To come home.

To be with his wife, Amy, whose father, Eddie Biedenbach, is a former NC State basketball star and also coached men’s basketball at UNC Asheville. Or to visit with one or more of his four boys. Two are in college, including Skyler, a star forward for a Quinnipiac University Bobcats team that is among the best—if not the best—in college hockey.

“My life is basically at the rink and then at home,” says Brind’Amour, talking to me from his car—in that line of cars filled with people waiting to pick up their children.

Hockey fans around the state have embraced Brind’Amour because, well, he has embraced them, and their beloved Hurricanes. His love for North Carolina and the Triangle is manifest in the team, in its relentless style and, yes, in its signature toughness and consistency.

The Canes are in line for a playoff berth but, as the coach said, there’s still a long way to go. Rest assured, however, Brind’Amour will do everything he can to help the franchise win another Stanley Cup.

Because, he says, “this is my home.” John Francis Trump is a freelance writer and author of “Still & Barrel: Craft Spirits in the Old North State.” He and his family live in Cary.